This is a chapter in my Book Serialisation project. You’re new here? You can start at the beginning and navigate around using this Table of Contents if you like.

Quick recap: We’ve already covered a lot of the risks and terrors inherent in collapse that are likely to be ahead, and the last two chapters - Spiritual and Liminality - provide two mindsets we’ll need to navigate things to “better”. But I’ve avoided answering a question that looms over all of it…

The audio version is at the bottom, available only to subscribers. Ditto the conversation in the comments section where we workshop things together.

<Previous Chapter | Table of Contents | Next Chapter

DEATH

“May we apprentice ourselves to the curve of our own disappearance.”

- David Whyte

“You cannot go around saying to people that there’s a 100 per cent chance they’re going to die.”

- President Orlean in Don’t Look Up

*

Q: Are we all going to die?

This question might have been hovering for you: Will we die? And if so, only some of us? Who exactly? How soon? How hellishly?

I’ve always been perplexed by the way this sticky issue is wholly avoided in climate collapse conversations. But, of course, it is always there, hanging over us, like the sword of Damocles. It’s the ultimate, unutterable, point, no?

For the purpose of this book (for we have committed to full-frontal truth here), we will have to go there.

A bold, truth-based awareness of collapse slams us up against a bunch of different deaths. The first, of course, is the prospect of our own death, and that of our loved ones.

We will all die one day. We know this. In fact, to be human is to be the only species aware of its own mortality. At the same time, we are unable to live peaceably in this awareness. I mean, it’s tricky for a human to reflect on the absence of the very thing doing the reflecting. Sigmund Freud called this dilemma the “mortality paradox” and wrote, “It is indeed impossible to imagine our own death … [Therefore] at bottom no one believes in his own death1.”

We once had aging and dying rituals to help us navigate this paradox and to bring a reverence to the cycle of life. We shared wisdoms that put the brutal inevitability of our nonbeing into context, as part of this bigger cycle, allowing us to live courageously and fully alongside the fear and absurdity. But, sigh, our secular, individualist culture has replaced these rituals and wisdoms with an obsession with youth and a bunch of thoroughly avoidant longevity protocols that shield us from facing this “certain-uncertainty”, as the philosopher Kierkegaard called it.

Which, of course, leaves us thoroughly ill-equipped for death. And for living, in fact.

*

The second death we’re forced to face is that of humanity.

Collapse seriously threatens our species’ extinction. Many scientists and other theorists argue this is what collapse amounts to - a sixth extinction2.

*

Of these two deaths, the latter is the more devastating to sit with, to my mind. Humanity has always been a wholly bigger and nobler project than my individual life and I derive comfort and meaning from its omnipotence. I will die, but the grand experiment that is the human endeavour will live on. How magnificent!

When I think about the very real possibility of humanity ending, I feel my heart splinter. What a crying bloody shame to have a thing so intricately calibrated, so mysterious and beautifully paradoxical come to an end.

It feels more than a shame. It feels like the most original of sins. What if we actually fucked this whole thing up, and on our watch? What if we ruined this gift we were granted, threw the whole lot irreversibly under the truck for ourselves and the innocent children to come, the animals, and everything else that makes up the web of life on Mother Earth?

I think many of us feel this moral injury more than we allow our souls to acknowledge. Deep within us is a custodian instinct, I believe.

*

“We are not the dinosaurs - we are the meteor. We are not only in danger - we are the danger.” - Antonio Guterres, Secretary-General of the United Nations

*

When I first began to really feel into the shock, guilt and grief of this momentous truth I was reminded of a line that William Boroughs gave to a journalist when asked to explain the meaning of his book titled Naked Lunch. It’s the “frozen moment when everyone sees what is on the end of every fork,” he said. I think collapse - and being forced to confront death like this - plants us at our collective naked lunch, in a frozen moment together, facing what we’ve been blindly eating up for too long.

*

Before we go further, I’d love to get granular with a particular collapse that only hit my radar recently. I think pausing on it for a bit will land some of what we’re talking about already.

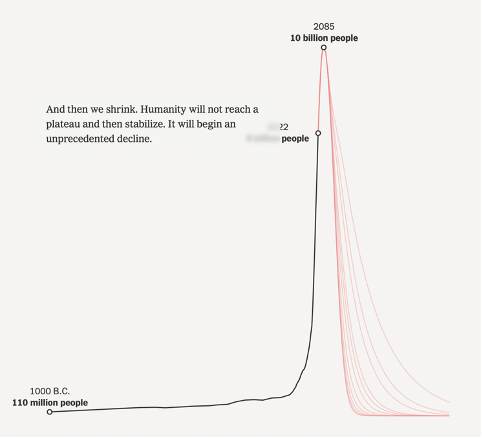

In the past 12 months or so, a number of respected global institutes3, including the United Nations, released reports that show global population will peak between nine and 10 billion aching messy humans by 2080. Some projections say it will happen as early as 2040 or 2050. Regardless, soon after this peak is reached, the world’s population will start to decline rapidly… toward its potential extinction.

Economists at the Population Research Center at the University of Texas released modelling with an aggressive looking bell curve chart featuring a hectic descent post-peak. The scientist who led the research explained that because most demographers look ahead only to 2100, there is no consensus on exactly how quickly populations will fall after that. But he speculated that since “over the past 100 years, the global population quadrupled, from two billion to eight billion, as long as life continues as it has…then in the 22nd or 23rd century, our decline could be just as steep as our rise.” You can do the calculations on this one - this would mean a “decline” of more than 6 billion people (from that 10 billion peak) by the end of next century.

Other theories suggest decline is likely to brake at the point at which humanity can exist within the earth’s carrying capacity once again. This figure seems to be around one billion people (some estimates are as high as three billion)4. Taken from another angle, Nate Hagens has calculated how many people the planet can hold without fossil fuels, which is where he argues we will land. Again, one billion people.